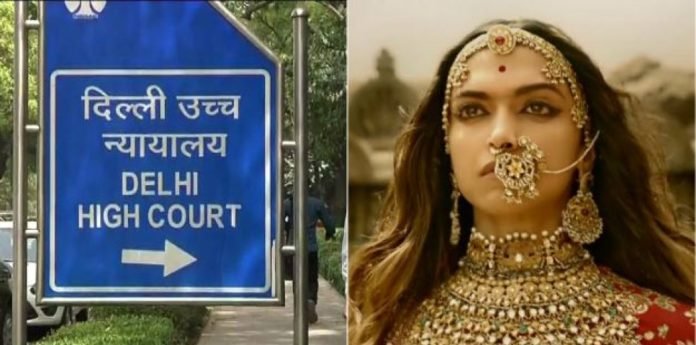

The Delhi High Court vide its judgement dated February 22, 2018 dismissed the writ petition filed by Swami Agnivesh seeking directions to the CBFC to take appropriate steps to stop glorification of the practice of ‘Sati’ by deleting the relevant scenes from the film ‘Padmaavat’. [Read judgement here]

The bench comprised of acting Chief Justice Ms. Gita Mittal and Justice C. Hari Shankar.

The petitioner had premised his petition on the basis of two articles; one by Ms. Charu Gupta in the Indian Express titled ‘United in misogny’ and the other was the article written by actor Swara Bhaskar in the Wire captioned ‘At the End of Your Magnum Opus… I felt reduced to a vagina – only’. The petitioner submitted that after reading these articles relating to the film ‘Padmaavat’, he himself wanted to check the veracity of the contents made therein regarding glorification of the practices of ‘Sati’ and ‘Jauhar’ and therefore personally watched the film after which he was convinced that the abhorrent practice of ‘Sati’ has been glorified out of proportion in the movie.

The petitioner further contended that in the film Padmaavat, the respondent nos.4 and 5 have glorified the act of “self-immolation in one of the most elaborately choreographed ‘Sati’ or ‘Jauhar’ scenes in the history of Indian cinema” which act constitutes ‘glorification’ under the provisions of the Commission of Sati (Prevention) Act, 1987.

The Court referred to the multiple challenges before the Supreme Court including the multiple petitions filed by Manohar Lal Sharma vs Sanjay Leela Bhansali & Ors which were dismissed by the Supreme Court. The Court then relied on the Supreme Court’s decision in Viacom 18 Media Private Limited & Ors vs Union of India where the certificate issued by the CBFC was extracted by the Supreme Court.

The Court observed that the CBFC had applied its mind before grant of the certificate and had left it to the sensibilities and evaluation by the parents or guardians as to whether their child below 12 years of age should be allowed to view the film. The Court also referred to the two disclaimers in the film which read as follows:

“Disclaimer –I

The Film ‘Padmaavat’ is inspired from the epic poem Padmavat, written by Malik Muhammad Jayasi, which is considered a work of fiction. This Film does not infer or claim historical authenticity or accuracy in terms of the names of the places, characters, sequence of events, locations, spoken languages, dance forms, costumes and/or such other details. We do not intend to disrespect, impair or disparage the beliefs, feelings, sentiments of any person(s), community(ies) and their culture(s), custom(s), practice(s) and tradition(s).

Disclaimer-II

This Film does not intend to encourage or support ‘Sati’ or such other practices.”

The court laid emphasis on the second disclaimer which clearly declares the intent of the director that the film in no manner encourages or supports ‘Sati’ or any such practice.

With respect to the petitioner’s contention on the glorification of Sati under the provisions of the Commission of Sati (Prevention) Act, 1987, the Court referred to the definition of ‘glorification’ under the Act under Section 2(b) which is as under:

(b) “glorification” in relation to sati, whether such sati, was committed before or after the commencement of this Act, includes, among other things.-

(i) the observance of any ceremony or the taking out of a procession in connection with the commission of sati; or

(ii) the supporting, justifying or propagating the practice of sati in any manner; or….

The Court observed that a bare reading of the definition makes it clear that the reference in the statute is to the actual practice of ‘Sati’ and not to a visual depiction of an imaginary work of fiction as portrayed in the film.

The Court further observed that the petition was filed after the film received the certification under the Cinematograph Act, 1953 after protracted litigation and a close scrutiny by experts. The Board has exercised its discretion carefully and not given a ‘U’ certificate for unrestricted viewing but granted a ‘U/A’ certification. The Court further observed that the film has already released and if the petitioner had any grievance, he could have placed it before the CBFC at the appropriate time.

With respect to the two articles relied on by the petitioner, the Court stated that it is their view and perception regarding the film and the petitioner is entitled to have a similar opinion and agree with them. The Court said “It is apparent that at the same time, there are several others who have considered the impact of the film from other perspectives and do not share the views the petitioner or the two authors. Certainly writs cannot be issued against artistic works premised on individual perceptions.”

The Court laid emphasis on the reliance by Supreme Court of the judgement in Nachiketa Walhekar v. Central Board of Film Certification & Anr, where the issue of artistic expression was observed as under:

“Be it noted, a film or a drama or a novel or a book is a creation of art. An artist has his own freedom to express himself in a manner which is not prohibited in law and such prohibitions are not read by implication to crucify the rights of expressive mind. The human history records that there are many authors who express their thoughts according to the choice of their words, phrases, expressions and also create characters who may look absolutely different than an ordinary man would conceive of. A thought provoking film should never mean that it has to be didactic or in any way puritanical. It can be expressive and provoking the conscious or the sub-conscious thoughts of the viewer. If there has to be any limitation, that has to be as per the prescription in law.”

While upholding the sanctity of the CBFC certificate granted to the film, the Court observed that the Supreme Court in the matter of Viacom vs UOI has held that there would be a prima facie presumption that the concerned authority has taken into account all the Guidelines before issuance of the certificate. The order stands recorded with regard to the certificate accorded by the Board of Film Certification to the film ‘Padmaavat’ and binds the present consideration.

The Court further referred to the Supreme Court’s decision in the case of Bobby Art International vs Om Pal Singh Hoon with respect to the object and impact of the CBFC Guidelines:

“22. The guidelines aforementioned have been carefully drawn. They require the authorities concerned with film certification to be responsive to the values and standards of society and take note of social change. They are required to ensure that “artistic expression and creative freedom are not unduly curbed”. The film must be “judged in its entirety from the point of view of its overall impact”. It must also be judged in the light of the period depicted and the contemporary standards of the people to whom it relates, but it must not deprave the morality of the audience. Clause 2 requires that human sensibilities are not offended by vulgarity, obscenity or depravity, that scenes degrading or denigrating women are not presented and scenes of sexual violence against women are avoided, but if such scenes are germane to the theme, they be reduced to a minimum and not particularised.

23.The guidelines are broad standards. They cannot be read as one would read a statute. Within the breadth of their parameters the certification authorities have discretion. The specific sub-clauses of clause 2 of the guidelines cannot overweigh the sweep of clauses 1 and 3 and, indeed, of sub-clause (ix) of clause (2). Where the theme is of social relevance, it must be allowed to prevail.

Such a theme does not offend human sensibilities nor extol the degradation or denigration of women. It is to this end that sub-clause (ix) of clause 2 permits scenes of sexual violence against women, reduced to a minimum and without details, if relevant to the theme. What that minimum and lack of details should be is left to the good sense of the certification authorities, to be determined in the light of the relevance of the social theme of the film.”

The Court noted that in the present case the CBFC has scrutinized the film in light of the statutory provisions and Guidelines. Hence the petition was dismissed.

Image source: here