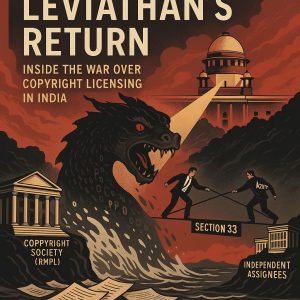

The Delhi High Court’s Division Bench judgment in Azure Hospitality Private Limited v. Phonographic Performance Limited, followed by the Supreme Court’s partial stay order in PPL v. Azure (SLP(C) No. 10977/2025), has reignited a fundamental question that has plagued India’s copyright ecosystem since the 1994 amendment: Can entities, through creative legal structuring, essentially bypass the regulatory framework intended to govern systematic licensing of copyrighted works through registered copyright societies? This case represents just the latest chapter in the ongoing saga of PPL’s existence in a regulatory twilight zone – claiming the absolute rights of ownership while dodging the oversight mechanisms consciously established by Parliament for entities “in the business of issuing licenses.”

I had previously written on this issue for the blog in concern with the Madras HC’s judgment in Novex v. DXC, highlighting my views on the issue.

From Individual Rights to the Collective Leviathan: The Section 33 Dilemma

Section 33(1) of the Copyright Act, with its seemingly straightforward prohibition, has been at the center of a longstanding interpretive battle:

“No person or association of persons shall, after coming into force of the Copyright (Amendment) Act, 1994 commence or, carry on the business of issuing or granting licences in respect of any work in which copyright subsists or in respect of any other rights conferred by this Act except under or in accordance with the registration granted under sub-section (3).”

The provision includes a crucial first proviso that has become the trojan horse through which licensing has been carried out outside regulatory oversight:

“Provided that an owner of copyright shall, in his individual capacity, continue to have the right to grant licences in respect of his own works consistent with his obligations as a member of the registered copyright society.”

For years, entities like PPL and Novex have exploited what I call the “assignment-proviso loophole” – obtaining assignments from original copyright owners, claiming ownership status under Section 18(2), and then asserting that the first proviso to Section 33(1) exempts them entirely from the regulatory framework established for copyright societies. This clever legal maneuver effectively created a parallel, unregulated track for entities engaged in the very activities that Section 33 was designed to regulate. The result is that even individual owners now have to suffer the cost of this interpretive lacunae.

Historically, the Delhi High Court in Novex Communication v. Lemon Tree Hotels (2019) and subsequently in Phonographic Performance Ltd. v. Canvas Communication (2021) validated PPL and Novex’s approach, seemingly allowing private licensing cartels to flourish outside any meaningful regulatory oversight – free to set arbitrary tariffs, enforce them through litigation, and operate without the transparency and accountability mechanisms established in Chapter VII. Even the Bombay High Court aligned with this interpretive approach in Novex Communications v. Trade Wings Hotel (2024), emphasizing the distinct operational spheres of Sections 30 and 33, observing that Section 30 forms part of Chapter VI (addressing licensing by owners), and Section 33 is part of Chapter VII (addressing copyright societies). This structural distinction, according to the court, underscored that these provisions were intended to address different aspects of copyright exploitation, with Section 33 not limiting the substantive rights established under Section 30. It observed that an interpretation that restricted owners’ licensing rights would be contrary to this purpose and would impermissibly curtail the property rights inherent in copyright ownership.

The Madras High Court’s Approach – Now Consigned to Oblivion

What’s particularly remarkable about this interpretive battle is that the Madras High Court, in my very personal opinion, actually got it right. In Novex Communications v. DXC Technology (2021), the court cut through the clever legal structuring to focus on the substantive nature of the activities involved. It recognized that the “business of issuing licenses” – regardless of whether conducted by an original owner, assignee, or agent – is what triggers the regulatory requirements of Section 33(1). The court understood that allowing entities to circumvent this framework through assignments would defeat the legislative purpose.

Yet this sound interpretation was effectively neutralized when, in a curious twist, Novex managed to have the judgment quashed by consent. On March 10, 2025, the Division Bench of the Madras High Court passed a consent order in which:

“The impugned order dated 8.12.2021 is quashed and set aside; The suits are restored to file; The suits are allowed to be withdrawn unconditionally; The statement of Shri Raman that plaintiff has no claim whatsoever against defendant in the respective appeals up to today is also accepted.”

This convenient settlement prevented the Madras High Court’s interpretation from establishing judicial precedent, allowing entities like PPL and Novex to continue operating in their self-created regulatory limbo. In any case, the “consent” mechanism enabling quashing of a judgment raises serious questions about private entities effectively negotiating their way out of unfavorable precedents that accurately interpreted regulatory statutes.

The Delhi High Court Division Bench’s Decision: Closing the Loophole

Against this backdrop, the Division Bench judgment in Azure v. PPL represents nothing short of a jurisprudential revolt. Justice C. Hari Shankar, showing intellectual honesty by implicitly reversing his own position in Canvas Communication, delivered a judgment that methodically dismantles the assignment-proviso loophole.

The Division Bench’s analysis centers on three key determinations:

- The court held that Section 33(1) creates an “absolute and non-negotiable” obligation for any person carrying on the “business of issuing or granting licenses” to do so in accordance with the registration granted under Section 33(3). This proscription applies to “any person” – including owners or assignees operating at scale.

- The court held that the first proviso “proceeds on the accepted premise that the owner of copyright, who carries on the business of issuing or granting licences in respect of copyrighted works, is a member of a registered copyright society.” The phrase “consistent with his obligations as a member” is not merely limiting rights of existing members, but presupposing membership for those engaged in systematic licensing.

- The court emphasized that the phrase “or in respect of any other rights conferred by this Act” encompasses the rights conferred by Section 30, meaning that even when exercising the right to license under Section 30, entities engaged in the “business” of doing so must comply with the regulatory requirements.

- The court noted that Section 33(1) requires entities engaged in the business of issuing licenses to do so “in accordance with the registration granted under Section 33(3).” This language, according to the court, meant that such entities must either be registered copyright societies themselves or act in conformity with the registration granted to an existing copyright society.

Based on this analysis, the Division Bench concluded that PPL, which admittedly carried on the business of issuing licenses for sound recordings, could only do so in accordance with the registration granted under Section 33(3). Since PPL was neither a registered copyright society nor a member of one, it could not legally issue licenses for the sound recordings in its repertoire.

However, the Division Bench did not simply dismiss PPL’s claims. Instead, it crafted a remedy that, in its opinion best balanced the competing interests at stake. The court held:

- PPL, as the assignee and therefore owner of copyright in the sound recordings, retained legal rights in those recordings.

- However, PPL could only issue licenses for those recordings “in accordance with” the registration granted to RMPL, the registered copyright society for sound recordings.

- Therefore, Azure would be required to make payments to PPL for using the sound recordings in PPL’s repertoire, but these payments would be “as per the Tariff of RMPL, as displayed on its website, and in accordance with the terms thereof, as if PPL were a member of RMPL.”

The problematic bit is that this was done without a prayer in respect thereof, perhaps something that holds enormous essence in commercial suits.

The Supreme Court’s Surgical Intervention

The Supreme Court’s order in PPL v. Azure reflects a restrained and surgical intervention. The Court stayed only “the impugned directions in terms of paragraph 27 of the impugned order” – specifically, the direction for Azure to make payments to PPL as per RMPL’s tariff rates, as the same was not even prayed for by the Plaintiff.

This limited stay suggests that the Supreme Court has concerns about the specific remedy crafted by the Division Bench (without a prayer thereof in the suit), rather than its underlying legal analysis. In my opinion, the Court appears to recognize that directing payment at RMPL’s rates creates a problematic hybrid arrangement without clear statutory foundation and a prayer – effectively forcing PPL to adhere to tariffs set by a society of which it is not a member.

The Supreme Court’s stay of this specific aspect of the judgment suggests similar concerns about the remedy’s foundation and practicability. A more coherent approach might have been to enforce the regulatory requirements of Section 33 directly – requiring PPL to either register as a copyright society (if exceptional circumstances warrant multiple societies under the “ordinarily” exception in the proviso to Section 33(3)) or become a member of RMPL.

Crucially, the Court also clarified that “notwithstanding this order of stay, the order dated 3rd March 2025 passed by the learned Single Judge will not operate” – meaning that neither the original injunction in favor of PPL nor the Division Bench’s modified order would be operative during the pendency of the appeal.

This nuanced approach leaves the substantive legal question – whether entities like PPL must comply with the regulatory framework established by Section 33 – very much alive. The Court has, at least for now, neither endorsed the “parallel track” approach that has allowed systematic licensing outside the regulatory framework, nor fully embraced the Division Bench’s specific solution, leaving the following questions open for final determination:

- Can entities engage in the systematic business of issuing licenses without complying with the regulatory framework established by Section 33?

- Does the first proviso to Section 33(1) create an exception to the main prohibition or merely preserve a limited right for owners who are members of copyright societies?

- What is the appropriate remedy when entities engage in licensing activities without complying with the regulatory requirements?

The answers to these questions will shape the future of collective management in India, with significant implications for copyright owners, users, and the broader public interest in access to creative works.

The “Both Shores” Problem

The Division Bench’s judgment brings into sharp focus what I call the “both shores” problem: entities like PPL attempting to simultaneously claim the benefits of two mutually exclusive regulatory positions.

Consider PPL’s contradictory positions:

- On one shore, it claims to be an owner of copyright by virtue of assignments, entitled to issue licenses outside the regulatory framework established by Section 33, setting its own tariffs without regulatory oversight.

- On the other shore, it has applied for re-registration as a copyright society under Section 33, seeking to operate within the very regulatory framework it claims doesn’t apply to its current operations.

- Meanwhile, it floats between these shores through litigation, asserting whichever position is more advantageous in a given case.

This dual positioning creates a textbook case of regulatory arbitrage. It allows PPL to selectively choose the benefits of each regulatory framework while avoiding their respective constraints – precisely the sort of gaming that regulatory systems are designed to prevent.

What makes this particularly egregious is that PPL has a long history of strategic regulatory positioning. After the 2012 Amendment required re-registration of copyright societies with more stringent regulatory oversight, PPL initially withdrew its application, choosing to operate as an “assignee” outside the regulatory framework. Yet simultaneously, it has been seeking re-registration as a copyright society since 2018, challenging the registration of RMPL (Recorded Music Performance Limited) – the currently registered society for sound recordings.

The “both shores” problem is particularly troubling given the explicit concerns about PPL’s operations raised in the 227th Report of the Parliamentary Standing Committee on the Copyright (Amendment) Bill, 2010:

“The Committee would like to point out that even during its deliberations with the copyright societies especially the Phonographic Performance Ltd (PPL) and the Indian Performing Rights Society Limited (IPRS), it was felt that they were not very forthcoming about their tariff schemes in spite of specific queries in this regard.”

These concerns directly led to the introduction of Section 33A, requiring copyright societies to publish their tariff schemes and establishing an appellate mechanism for challenging unreasonable tariffs. Allowing entities to sidestep these requirements through legal structuring completely undermines the legislative intent to establish transparency and accountability in collective licensing.

The 1994 and 2012 amendments to the Copyright Act reflect a clear and consistent legislative intent to establish a comprehensive regulatory framework for entities engaged in the systematic licensing of copyrighted works. This intent is evident in:

- The introduction of Chapter VII in 1994, establishing the registration requirement for entities engaged in the “business of issuing licenses”

- The strengthening of this framework in 2012, with enhanced requirements for transparency, accountability, and author participation

- The explicit concerns raised in the Parliamentary Standing Committee Report about the opacity and arbitrariness of tariff-setting by entities like PPL

This regulatory intent would be completely defeated if entities could simply obtain assignments and thereby bypass the entire regulatory framework. The result would be precisely what Parliament sought to prevent: monopolistic entities issuing licenses at arbitrary rates without transparency or accountability.

The Division Bench’s interpretation, by focusing on the substantive nature of the activities rather than the formal legal structure, aligns with this regulatory intent. It recognizes that the phrase “business of issuing or granting licenses” encompasses all systematic, commercial licensing activities, regardless of whether conducted by original owners, assignees, or agents.

I wouldn’t stop short, however, to admit that the Division Bench’s decision comes with its own misinterpretations.

The Division Bench’s interpretation of the first proviso to Section 33(1) as presupposing membership in a copyright society represents a significant interpretive leap. The proviso states that an owner shall “continue to have the right to grant licenses in respect of his own works consistent with his obligations as a member of the registered copyright society.” While this language references obligations as a member, it does not explicitly require membership as a precondition for licensing in an individual capacity. The phrase “consistent with his obligations” could be read as applying only to those owners who happen to be members, rather than requiring all owners engaged in licensing to become members. Not allowing licensing by owners in their individual capacity and only in respect of their individual works, would effectively eviscerate voluntary licensing, and would only permit licensing based on regulated tariffs. This was never the intent. Regulatory tariffs are only desirable in the case of collective licensing, or where there is a structural business of issuing licenses of works of multiple copyright holders in a bundled manner, to allow for transparent and affordable dissemination.

The Way Forward: From Regulatory Twilight to Regulatory Clarity

The controversy surrounding Section 33 is not merely academic – it has profound practical implications for copyright owners, users, and the broader cultural ecosystem. In my view, a coherent interpretation of Section 33 would include the following elements:

- When an entity engages in the systematic “business” of issuing licenses (as opposed to occasional, individual licensing), it triggers the regulatory requirements of Section 33(1), regardless of its formal legal status.

- Such entities must either register as copyright societies or become members of registered societies; they cannot operate in a regulatory no-man’s-land.

- The first proviso to Section 33(1) preserves individual licensing rights for owners individually qua their own works, as against by bundling their works with other’s works, but does not create a parallel, unregulated track for entities engaged in systematic licensing activities.

- The remedy for non-compliance should be based on the existing statutory framework, rather than judicial creation of hybrid arrangements.

This interpretation would close the loophole that has allowed entities to operate outside the regulatory framework while engaging in the very activities that the framework was designed to regulate.

Views are personal.

(Image generated on Dall-E)

Comments are closed.