INTRODUCTION

Recently, Justice A.S. Chandurkar of the Bombay High Court delivered his final verdict on 20.09.2024 as the third referral judge over the issue of constitutionality of Rule 3(1)(b)(v) of the 2023 amendment of Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021 and held that the impugned rule of 2021 as amended in 2023 is liable to be struck down, thereby rendering in a 2:1 majority opinion for striking down the said rule.

The recent follow-up judgment continues the scrutiny over Rule 3(1)(b)(v) of the 2023 amendment. This rule, which mandates that intermediaries remove content flagged as “fake or misleading” by the Fact Check Unit (FCU), has been met with considerable debate. At the heart of the case is a balancing act between free speech and the government’s prerogative to control misinformation concerning its business.

Following a split decision by Justices G.S. Patel and Dr. Neela Gokhale, this judgment provides further insight into procedural safeguards, due process, and specific constitutional standards applicable to intermediary regulation. The ruling elucidates a nuanced view of intermediary obligations and reaffirms the need for precise restrictions on free speech in digital governance.

BACKGROUND

The amendment to The Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021 notified in April 2023 did majorly did two things: firstly, they brought in a legal framework for the online gaming eco-system and secondly, more crucially, introduced a legal mechanism for the government to fact-check online content pertaining to “government business”.

Ever since the coming into effect of these rules, they have been a question of debate and controversy, specifically the Rule 3(1)(b)(v) of the IT Rules 2021 or commonly referred to as the “FACT CHECK UNIT RULE”.

The Rule mandated intermediaries such as social media platforms “to not to publish, share or host fake, false or misleading information in respect of any business of the Central Government”.

These amendments sparked worries that the FCU would effectively grant the government unilateral authority to determine the truth regarding its own affairs making it the “sole arbiter of truth”.

Therefore, in furtherance, the critics referred to this rule as draconian in nature and being violative of Articles 14, 19(1)(a) and (g) and 21 of the Constitution of India and Section 79 and Section 87(2)(z) and (zg) of the Information Technology Act, 2000 (“IT Act”).

While a section of the society categorically welcomed the formulation of the Fact check unit due to widespread prevalent fake news across sections in different forms of media- particularly the social media.

However, due to the solemn concerns regarding the government becoming the unilateral authority to determine the truth regarding its own affairs, the said rule 3(1)(b)(v) of the IT Rules 2021 was challenged before the Bombay High Court through a batch of Writ Petitions filed under Article 226 of the Constitution of India.

ISSUES RAISED BEFORE THE HIGH COURT

The amendment to Rule 3(1)(b)(v) of the IT Rules 2021 essentially expanded the general term “fake news” to include fake news involving government business.

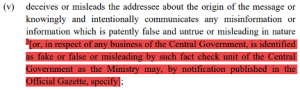

This provision, when enacted in 2021, referred to “…knowingly and intentionally communicates any information which is patently false or misleading in nature but may reasonably be perceived as a fact”.[1]

By the 2023 amendment, after the word “nature”, the words [“or, in respect of any business of the Central Government, is identified as fake or false or misleading by such fact check unit of the Central Government as the Ministry may, by notification published in the Official Gazette, specify”] were inserted.

A bare comparison of the two verbatim is as under:

![]()

– The 2021 Rules.

Vs.

– The 2023 Amendment.

The thrust of the challenge of the impugned Rule raised by the Petitioners was that this amendment would construe a ‘chilling effect’ upon the freedom of speech and expression of the Petitioners, guaranteed under Part III of the Constitution of India. The Petitioners were aggrieved by the impugned Rule vesting authority in a Fact Check Unit (“FCU”) to be notified by the Government to identify the veracity or otherwise of ‘information’, thereby alleging the Government to be the sole arbiter of truth in respect of any business related to itself.

Additionally, Section 69 of the IT Act empowers the government to issue directions to block public access to any information through any computer resource. The Rules were framed essentially in exercise of this power. However, no rule-making or legislation-making powers can be exercised by Parliament in a manner that is contrary to Part III of the Constitution, which deals with fundamental rights.

THE SPLIT VERDICT

The Bombay High Court examined if these Rules were violative of free speech, and were arbitrary in nature. The bench of Justices G S Patel and Neela Gokhale, presided over various hearing in this case and finally on 31st January, 2024 delivered split verdicts.

With Justice GS Patel holding the 2023 amendment to Rule 3(1)(b)(v) to be ultra vires and intending to strike it down and Justice Dr. Neela Gokhle upholding the constitutional validity of the said rule.

Read the detailed analysis of the Split verdict entailed in my previous article here: “Fact Check Unit: A Prelude to government censorship?”.

Since a split verdict was delivered, as per rules of the Bombay High Court, the case had to be heard afresh by a third judge whose opinion would create a majority and bring about a 2-1 verdict. On February 7, Bombay HC Chief Justice Devendra Kumar Upadhyaya assigned Justice Atul S Chandurkar as the third judge in the case.

THE QUESTION OF INTERIM RELIEF AND THE SLP BEFORE THE SUPREME COURT

At the time of pronouncement of the Division Bench’s order, the question arose whether Union of India would continue its undertaking initially made to the court about not notifying the FCU. The court asked for this question to be decided by the third judge who would be notified to hear the matter.

Therefore, before the beginning of the substantial hearing to decide the matter on merits, Justice Chandurkar had to deliver an interim opinion to decide if the Rules were to be stayed.

Justice Chandurkar on 11th March, 2024 opined that the balance of convenience favours the Union, considering the government’s submission about not using the FCU to censor political opinions, satire, and comedy. Additionally, he said, any action taken after notifying the FCU would be subject to the final outcome of the petition and wouldn’t cause irreversible damage.

Subsequently, the reconstituted bench of Justices GS Patel and Neela Gokhale pronounced the interim order on 13th March, 2024 after the third judge, Justice Chandurkar, opined that no case was made out for interim relief until he decides the clutch of petitions.

Aggrieved by the majority order of the Bombay High Court concerning the implementation of the Rules, the Petitioners moved the Supreme Court challenging the refusal of the Bombay High Court to grant interim relief.

However, just a day before the SC was to hear the appeal against rejection of stay, the Centre notified the 2023 Rules in the official gazette. Before the hearing, MeitY on 20th March, vide Gazette Notification and powers conferred under Rule 3(1)(b)(v) of IT Amendment rules, notified the Fact Check Unit under the Press Information Bureau of the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting as the fact check unit of the Central Government for the purposes of the said sub-clause, in respect of any business of the Central Government.

The bench of Chief Justices DY Chandrachud, Justices JB Pardiwala, and Manoj Misra set aside the March 11 and 13 order of the Bombay High Court refusing to stay the implementation of the Rules and the consequential order allowing the Centre to notify the FCU till the Bombay High Court finally decides the challenges to the IT Rules amendment 2023.

ABSTRACT OF THE JUDGEMENT

The judgment encompasses a detailed examination of constitutional guarantees under Articles 14, 19(1)(a), and 19(1)(g), procedural fairness, and operational burdens on intermediaries.

- Definition of “Business of the Central Government”:

- The Court refined the interpretation of “business of the central government”, limiting its scope strictly to official government operations, as opposed to broad political discourse or criticism. This interpretation is aimed at ensuring that Rule 3(1)(b)(v) does not apply to a wide range of public content but remains confined to content closely associated with governmental activities.

- The Implication: By confining the term’s scope, the judgment seeks to avert overreach, about the potential for the rule to be used as a tool for “arbitrary censorship”.

- Procedural Safeguards and Right to Challenge:

- The judgment acknowledges that the absence of an appeal or review mechanism within the FCU fails to provide procedural fairness to intermediaries and, by extension, to end users. The Court recommends establishing a review board or tribunal to allow intermediaries the right to challenge FCU orders.

- Natural Justice: This recommendation aligns with the principle of audi alteram partem (the right to be heard) and is reflective of broader procedural rights that guard against executive overreach. This suggestion builds on Justice Patel’s earlier critique, emphasizing that natural justice requires a fair hearing before any adverse action is finalized.

- Freedom of Speech and the Chilling Effect:

- The Court acknowledged the potential chilling effect created by vague and over broad terms like “fake” and “misleading.” While it upheld the government’s interest in controlling misinformation, the Court emphasized that such restrictions must be implemented with clear standards to prevent undue suppression of lawful expression.

- Balancing Doctrine: The judgment reaffirms the “proportionality principle” as laid out in Modern Dental College v. State of Madhya Pradesh, emphasizing that restrictions on fundamental rights must be narrowly tailored and serve a legitimate purpose without being excessively intrusive.

CONSTITUTIONAL PRINCIPLES REASSURED AND REDEFINED

Constitutional Rights: Freedom of Speech, Equality, and Reasonableness

Article 19(1)(a): The judgment reiterates that freedom of speech is a fundamental right, central to the democratic fabric of India. The risk of chilling free speech due to ambiguous legal standards, suggesting that any legislation affecting speech must have clear and specific guidelines to avoid arbitrary application.

Reasonable Restrictions Under Article 19(2): The Court clarified that Rule 3(1)(b)(v) should be aligned with the reasonable restrictions under Article 19(2), specifically public order and the sovereignty of India. The judgment underscored that the rule must withstand the tests of necessity and proportionality, ensuring it does not infringe upon free speech disproportionately.

Article 14: The Court’s interpretation of Rule 3(1)(b)(v) as lacking sufficient safeguards against arbitrary action was based on equality before the law. The rule’s “open-ended terms” could lead to discriminatory enforcement, affecting different intermediaries and users disproportionately without transparent standards.

Principle of Natural Justice and Procedural Fairness

Audi Alteram Partem: Justice Patel’s view that the FCU, by being both enforcer and decision-maker, violates natural justice principles was addressed by the Court’s recommendation for a review mechanism. This aligns with the audi alteram partem principle, where every individual or entity affected by an adverse decision should have the opportunity to contest it.

Due Process Rights for Intermediaries: Recognizing the “inherent imbalance” in allowing the FCU unchecked authority, the Court suggested an independent tribunal for intermediary grievances. This recommendation draws from Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India, wherein due process was extended to administrative actions affecting fundamental rights.

Vagueness, Overbreadth, and Overreach

Interpretation of Ambiguous Terms: The Court scrutinized the terms “fake” and “misleading,” emphasizing that such terms are vague and subject to interpretation, which can lead to arbitrary and inconsistent application. Justice Patel had previously noted that these terms failed the constitutional test of clarity, leading to unpredictable standards.

Doctrine of Overbreadth: This doctrine, invoked in Shreya Singhal v. Union of India, calls for precision in drafting laws that restrict speech. The judgment reasserts this by confining the applicability of Rule 3(1)(b)(v) to content tied directly to government operations, thereby ensuring that over broad language does not sweep in legitimate discourse.

PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS FOR INTERMEDIARIES AND BUSINESSES

Operational Compliance and Definition Narrowing:

By narrowing the definition of “business of the central government,” intermediaries can focus on moderating content directly related to government activities. This refined scope provides clarity, reducing self-censorship tendencies by allowing intermediaries to avoid moderating generalized political commentary.

Implementation Cost: However, smaller intermediaries might still face substantial operational challenges, as tracking compliance under potentially vague standards remains complex and resource-intensive.

Procedural Costs and Legal Recourse:

The establishment of an appeals mechanism introduces an additional layer of compliance for intermediaries. Smaller platforms may face financial burdens if they are forced to engage in legal proceedings for each FCU notification. While the right to appeal offers fairness, it may also add to compliance costs.

Risk of Over-Censorship:

Justice Patel’s concern over a chilling effect remains relevant, as intermediaries may still lean towards removing content proactively. Although the Court’s narrowing of the rule’s scope helps mitigate this effect, the overall risk of self-censorship cannot be completely eliminated.

LAW ACROSS INTERNATIONAL JURISDICTIONS

United States– Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act offers broader “safe harbor protection”, shielding intermediaries from liability for third-party content and permitting them to moderate content without restrictive government intervention. The judgment’s focus on procedural safeguards aligns somewhat with Section 230, although Indian law provides fewer protections for intermediaries.

European Union– The Digital Services Act (DSA) mandates robust procedural standards, including appeals and transparency in content decisions. The DSA’s accountability-focused approach parallels the Bombay High Court’s suggestion of procedural review, which could offer a model for India’s own intermediary framework.

United Kingdom– The Online Safety Bill emphasizes intermediary responsibility for controlling harmful content but mandates procedural fairness for content moderation decisions. The Bombay High Court’s call for procedural safeguards shows a similar inclination toward balanced regulation, ensuring both government oversight and intermediary rights.

GOING FORWARD- FUTURE SCOPE AND POTENTIAL DEVELOPMENTS

Legislative Refinements and Policy Adjustments:

The Court’s recommendation for a procedural review body may prompt legislative amendments to introduce an appeal mechanism, ensuring fair and transparent implementation of Rule 3(1)(b)(v).

Guidelines for Procedural Safeguards:

Future regulations could include guidelines on procedural timelines, intermediary obligations for takedown requests, and the standards for appeal. Clearer provisions would ensure fair and consistent application, protecting both user rights and intermediary interests.

Alignment with Global Standards:

India may look to the EU’s DSA and the UK’s Online Safety Bill as models for balancing digital rights with responsible content moderation. Global alignment would provide consistency for international intermediaries, enhancing legal predictability in India’s digital space.

CONCLUSION

The Bombay High Court’s follow-up judgment on Rule 3(1)(b)(v) addresses fundamental concerns over free speech, intermediary liability, and governmental control of misinformation. Through a balanced approach that emphasizes due process and narrowly defined terms, the Court offers a nuanced solution that mitigates the risk of overreach while recognizing the need for legitimate misinformation control.

By refining procedural safeguards and clarifying the rule’s scope, the judgment takes an important step toward a transparent, balanced regulatory framework for India’s digital ecosystem. Legislative refinements and alignment with international standards will be essential in creating a fair digital

End note:

[1] Rule, 3(1)(b)(vi), the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021.

Image generated on Dall-E