Introduction:

It seems that the world of films and its expression and the sensitivity regarding religious issues do not go hand in hand. In the recent past with films like Kashmir Files, The Kerala Story, PK[i] etc, the Courts of law have upheld the creative freedom of expression that the medium of films offers. Often, the Courts approach such matters with grave sensitivity keeping in mind the diverse country of religions, that India is.

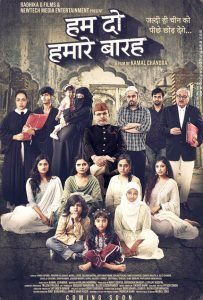

One such film is Hamare Baarah (previously titled as ‘Hum Do, Humare Baraah”) by director Kama. Chandra starring Annu Kapoor in a prominent role. After much controversy and proceedings before the Bombay High Court and the Supreme Court respectively, the film is slated to release on 21 June 2024.

Public Opinion & Outrage:

Prior to the release of the film, the film brought in outrage and dissent particularly from the Muslim community. It was put forth by various religious leaders of the community that the film connotes to false ideas as follows:

- In the Muslim community, women are treated as sex objects to procreate as many children as possible. This ideology is put forth because in the Quran, it is believed that a child is a gift of God and ‘the more the merrier.’

- The Muslim women are forced to give birth to children ignoring their personal needs, consent and health issues. They have no autonomy over their bodies.

- The Muslim community is not abiding the norms of family planning.

- The Muslim community does not respect its women and treats them poorly.

The Karnataka government went on to ban the release of the film for two weeks on the grounds that it could incite communal riots.

Before the Court of Law:

Bombay High Court – Azhar Basha Tamboli vs Ravi S. Gupta

Before the Bombay High Court, a petition[ii] was filed by Azhar Basha Tamboli alleging that the film in question is in contravention to the Cinematograph Act, 1952 as well as its release would violate Articles 19 (2) and Article 25 guaranteed under the Indian Constitution. Further, the administrative approval granted by the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) was challenged by the Petitioners.

The vacation court consisting of J. N.R Borkar and J. Kamal Khata on 5 June 2024, recorded its first order in the writ petition. Mr. Khandeparkar, the arguing counsel for the Petitioner while referring to the trailer of the film available on YouTube, averred that one scene refers to ‘Aayat 223’, a verse in the Quran, the holy book of the Muslims. Such direct reference to a holy book is equal to blasphemy and misreading of the verse. He further pointed out that the trailer does not contain any disclaimer to the certification granted by CBFC.

To this, Ms. Sethna representing CBFC relied on the certifications dated 23 January 2024 and 3 April 2024 wherein objectional scenes and dialogues in the film were deleted. It was also pointed out that the trailers released on YouTube and Book My Show websites were uncertified trailers and necessary action would be taken to take down such trailers after following the due process of the law.

The Court held that a prima facie case was made out by the Petitioner and passed an interim injunction restraining the film-makers from exhibiting, circulating, or making available for viewership to the general public the film in question till 14 June 2024.

Immediately, on 6 June 2024 a praecipe was moved by film-makers against the injunction passed ex parte on 5 June 2024. Senior Advocate Mr. Narichania representing the film-makers contended that such an order would cause severe financial loss to the film at the eleventh hour which is slated to release the following day. Thereby, a panel of three was set up including at least one member of the Muslim community to view the film and submit an informed opinion. Mr. Narichania further argued that the film has already received an approval from the CBFC after due consideration of its guidelines and has also been exhibited at the prestigious Cannes film festival.

Making an interesting observation that the first show is scheduled at 10:00 AM, the Court directed for a hearing at 9:00 AM in the interest of equity.

On 7 June 2024, the three-member committee set up by the Court requested for an extension of time until 12 June 2024 to provide a ‘well-reasoned and comprehensive response’.

It is a well-established principle that once a competent authority has approved the nationwide screening of a film, the opinion of any high-level committee holds no authority as they are not empowered to make such determinations. This is exemplified in the case of Priya Singh Paul vs Madhur Bhandarkar[iii], where it was held that the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) is the ultimate authority to assess the societal impact of a film, even in cases where sentiments may be perceived as hurt. Consistently, the courts have affirmed the CBFC’s jurisdiction and have entrusted it to adhere to its comprehensive guidelines concerning film certification. Therefore, when the CBFC has already granted certification to a film and subsequently it is restrained from release, it sets a precedent that could potentially subject film producers to undue coercion.

Consequently, the court granted permission to exhibit the revised version of the film on June 8, 2024, following the implementation of directed cuts, changes, and disclaimers.

Aggrieved by the permission to exhibit the film, the Petitioner went on to file a Special Leave Petition[iv] before the Supreme Court. The Petitioner went on to challenge the orders dated 6 and 7 June 2024 of the Bombay High Court by an SLP on 13 June 2024 which were dismissed considering that the matter is sub judice and until such time, the screening of the film was suspended. The Supreme Court did not delve into the merits of the case but directed the Bombay High Court to expedite its ruling on the pending writ petition.

Finally on June 19, 2024, the Court allowed the release of the film in question. Led by a division bench of J. B.P Colabawalla and J. Pooniwalla, various observations were made.

All relevant orders can be accessed here, here, here and here.

Various changes were put forth which were agreed by all the parties, including the interveners, thereby leading to the release of the film:

- The disclaimer will be shown at the beginning of the film for a duration of 12 seconds.

- The message reading “According to the sharia (law), Muslims are allowed to practice polygyny. According to the Quran, a man may have up to four legal wives only if there is fear of being unjust to non-married orphan girls. Even then, the husband is required to treat all wives equally if a man fears that he will not be able to meet these conditions then he is not allowed more than one wife.” together with its Hindi translation will be displayed on screen for a duration of 12 seconds.

- The words “Allah Hu Akbar” appearing in the Film shall be muted.

- The recitation of Ayat 223 which is recited in Arabic language at the inception of the Film, will be muted.

- The CBFC will upon receipt of the application for re-certification of the Film under Rule 31 of the Cinematograph (Certification) Rules, 2024, shall forthwith (and in any event no later than 12 Noon on 20 June 2024), grant a fresh certification based on the aforesaid changes.

- After such certification, the film-makers are at a liberty to exhibit the film in question.

Analysis:

Decoding various precedents of the Courts with respect to films, I observed that religion has been the bone of contention of many media litigations in the country. The ‘Kedarnath’ film case in Ramesh Chhabinath Mishra vs CBFC & Others[v], wherein it was averred that the sentiments of the Hindu community have been hurt by showing a Muslim-Hindu couple was dismissed by the Court of law. In fact, every case in the end accords highest recognition to the powers of CBFC and trusts its decision making. The case upheld the Sub-section (2) of Section 5B of the Cinematograph Act, 1952 as follows:

The objective of CBFC is to ensure the following:

a) the medium of film remains responsible and sensitive to the values and standards of society;

b) artistic expression and creative freedom are not unduly curbed;

c) certification is responsive to social change;

d) the medium of film provides clean and healthy entertainments; and

e) as far as possible, the film is of aesthetic value and cinematically of a good standard.

The High Court of Tamil Nadu in the case of Sony Pictures vs State of Tamil Nadu[vi] has dealt with the issue in relation to judicial overreach with respect to exhibition of films. In this case, the exhibition of the film, “The Da Vinci Code” was suspended for two months in Tamil Nadu on the ground that various sections of the Christian community have expressed their strong resentment against the alleged objectionable content of the film.

Through these judgments, it can be observed that the constitutional rights are accorded the highest importance. Of course, freedom of expression and creative communication, more so, for a film-maker occupies a very special position among constitutional guarantees. It does not include intolerance to express one’s views in the market place. There will be periods of renaissance in the history only when there is free inflow and outpouring of ideas, ideas which may even run counter to the dominant, traditional opinion must have for their free play, and this is the hypothesis on which free speech is built, that speech can rebut speech and propaganda will answer propaganda.

India is a diverse mixing pot of various religions, faiths and cultures. There should be a balance with respect to creative expression and religious harmony. Often such films attract attention prior to the release when they touch on religious issues. It should lie in the intent of the film-makers and the individuals behind projection of such ideas through the medium of films to draw a line between creative freedom and religious disharmony.

In some precedents, the question whether a court-appointed committee could review the certification granted by the CBFC, a statutory body in its own sense, have been left open and unanswered. One such case involved the film “Jolly LLB-2.” A lawyer filed a writ petition in the Bombay High Court, seeking the removal of specific scenes that he felt undermined the dignity of the judiciary. He also demanded an unconditional apology from the film’s producers and director for allegedly tarnishing the legal profession, arguing that this amounted to contempt. Based on two trailers and some images, the High Court seemed to agree, noting that the photographs indicated a lack of respect for the court’s authority. The court then appointed a three-member committee, including two lawyers, to watch the film and submit a report. The producers immediately appealed to the Supreme Court, challenging the committee’s formation and jurisdiction. However, after hearing arguments, the Supreme Court chose not to interfere, leaving the High Court to issue orders based on the committee’s findings. The committee’s report highlighted several scenes it deemed objectionable, including one where a shoe was thrown at a judge, which they concluded amounted to defamation and contempt of court. In a compromise and considering the film’s imminent release, the director agreed to make four cuts and modify the scenes, after which the CBFC was instructed to re-certify the movie. The petition in the Supreme Court was then withdrawn, leaving unresolved the question of whether a court-appointed committee could review the certification granted by the CBFC, a statutory body.

The statutory body that decides on the statutory authority responsible for certifying films for public exhibition, and for requiring cuts or modifications, is the Censor Board. Appeals can be made to an Appellate Tribunal, and the government has revisional powers under the Act.

With a statutory body like the CBFC in place, the doors of the judiciary should not be knocked upon for revision and re-consideration of films. The CBFC and it’s functioning as laid down in the Cinematograph Act, 1952 followed by the recent Cinematograph (Certification) Rules, 2024 follow a detailed and informed structure.

Section 5 (4) of the Act lays down the setting up of advisory panels to judge the effect of the films on the public. Such panels have distinguished individuals on board to examine the film thoroughly. While Section 5 B (1) of the Act lays down the golden principles of guidance in certifying films. From interests of sovereignty and integrity of the country, security of the state, ensuring friendly relations with foreign states, abstaining from defamation to maintaining decency, morality, the principles are in place. While the offence of defamation can be analysed and a person could be penalized for the same, what could incite a situation which affects the integrity of the nation is subjective. And when such situations boil down to religion and faith, it is appropriate to hold discussions by the Board with community leaders and informed individuals who can provide their opinions.

While the Rules in Rule 12 call upon the Board to hold symposia and seminars of film critics, film writers, community leaders and persons engaged in the film industry. Such inclusion of individuals connected to the film fraternity is essential. The Board ensures that the films are reviewed not only by government employees of the CBFC but the individuals who can gauge films, its impact and message deeply. Such rules in place should give an assurance and trust that even before a film is certified, it goes through various parameters of assessment by the Board.

Such cases are further an example of judicial overreach in India. The judiciary must strike a careful balance between maintaining public order and safeguarding artistic and expressive freedoms. By undermining the legitimacy of the certification of CBFC and pre-emptively banning films, these actions could suppress creative expression and narrow the range of narratives essential for a dynamic democracy.

End Notes:

[i] 2015 SCC Online Del 6479

[ii] Writ Petition No. 8072 of 2024 | Bombay High Court

[iii] 2017 (6) Mh. L.J 957

[iv] Special Leave to Appeal (C) No(s). 13061 & 13062/2024

[v] 2018 SCC Online BOM 18215

[vi] 2006 SCC Online Mad 591