The story begins in 2015 when one Mr. Gaurav Bakshi googled ‘Agarwal Packers and Movers’ to employ the renowned company to assist him with his relocation. Much to his dismay, his belongings were delivered in a deplorable condition and he realised that he had employed another Agarwal Packers and Movers which had appeared upon insertion of the words ‘Agarwal Packers and Movers’ (which is a registered trademark of DRS Logistics) in his google search query and had thus been deceived.

Mr. Bakshi might be one of many who may have been deceived into employing competitor companies thinking them to be or affiliated to be with DRS Logistics. To tackle the same DRS Logistics had filed a complaint against Google in the Delhi High Court pleading that Google be restrained from using or permitting the use of the plaintiff’s trademark and/or a name similar to the same as keywords or meta tags so as to infringe the plaintiff’s mark.

The Learned Single Judge ruled in favour of the plaintiff and found that the use of trademarks as keywords in the Google Ads Programme would amount to ‘use’ under the provisions of the Trade Marks Act, 1999 and thus, may constitute infringement. Further, it held that Google is not entitled to the defence of an intermediary under Section 79 of the Information Technology Act, 2000 as Google is an active participant in use of the trademarks of proprietors. This judgement has also been relied upon in Head Digital Works v. TicTok Skill Games and Makemytrip India v. Booking.com. The same was appealed in front of the Division Bench at the Hon’ble Delhi High Court which upheld the learned Single Judge’s judgement.

The judgement runs into 95 pages and is rich in case law relevant to understanding the Court’s rationale. Primarily, there are three main questions that have been answered.

(i) Does the use of a trademark as a keyword qualify as ‘Use’ under the Trademarks Act, 1999?

(ii) Will such use constitute infringement under the Act?

(iii) Can Google be held liable for contributory infringement in the given case?

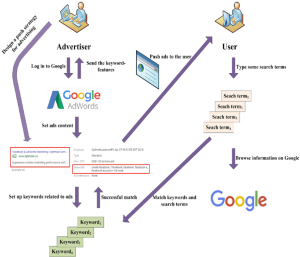

Before we deal with each of the questions set above categorically, it is essential to understand Google’s Ad Programme and how it works –

Previously known as Google AdWords, the Ads Programme is an advertising self-service platform managed by Google through which advertisers can create and display online advertisements with respect to their websites. The said advertisement comprises the Ad-heading/Ad-title & Ad-description (collectively referred to as ‘Ad-text’ which is editable in nature); and, URL or the website address. The sponsored link of DRS as displayed on the Search Engine Results Page (SERP), indicating the URL and the Ad, text is set out below:

“The service enables any economic operator, by means of the reservation of one or more keywords, to obtain the placing, in the event of a correspondence between one or more of those words and that/those entered as a request in the search engine by an internet user, of an advertising link to its site. That advertising link appears under the heading ‘sponsored links’, which is displayed either on the right-hand side of the screen, to the right of the natural results, or on the upper part of the screen, above the natural results.” Google France SARL and Google Inc. v. Louis Vuitton Malletier SA & Ors.

Below flowchart will help gain a brief understanding of the system:

Source: Liang, Jing & Yang, Haotian & Gao, Jiajia & Yue, Cai & Ge, Shilei & Qu, Boyang. (2019). MOPSO-based CNN for keyword selection on google ads.

Google provides a ‘Keyword Planner’ tool that is a statistical research tool built into the Ads Programme interface, which provides an integrated workflow to guide users through the process of finding keywords for creating new Ad groups and/or campaigns.

A user, who wishes to choose appropriate keywords for an advertisement, will have to type one or more descriptive words or phrases to solicit keyword ideas on the Keyword Planner. Thereafter, the tool displays keywords related to the word entered by the advertiser, along with the volume of monthly searches made on the same keyword and the additional keywords that could possibly be considered for use by the advertiser.

Illustration:

Google allows commercial entities to bid for individual search terms and, subject to certain factors, the ‘winner’ of the bid appears at the top of a relevant search for those terms. The ranking is not solely-reliant on the bid but on a multitude of factors including the ad quality score, context of the search, maximum cost-per-click etc.

Therefore, a situation may arise that upon a search query for the word ‘Audi’, competitor websites may rank higher than Audi’s website itself. An Illustration of the same is provided below.

The same issue is what was faced by DRS Logistics which led to the filing of this complaint.

(i) Does the use of a trademark as a keyword qualify as ‘Use’ under the Trademarks Act, 1999?

Google relied on the following judgments to prove that using a trademark as a keyword would not qualify as ‘use’ under the act.

- Veda Advantage Ltd. v. Malouf Group Enterprises Pvt. Ltd. (2013 SCC OnLine Del 2289)

- Intercity Group (NZ) Limited v. Nakedbus NZ Limited ( 2014 NZHC 124)

The premise of these judgements are on the reasoning that the primary function of a trademark is to serve as a source identifier of the goods or services; since the keywords are invisible, they do not serve to identify the source of any goods. The courts have thus concluded that use of a trademark as a keyword is not ‘use’ as a trademark at all. However, the judgments are based on foreign laws. The Veda Advantage case (supra) relies on the Trade Marks Act, 1995 as in force in Australia which does not include the same provisions as the Trade Marks Act in force in India (Hereinafter referred to as ‘TM act’).

As per Section 120 of the Australian Trade Marks Act, a trademark is infringed only if a mark is used “in such a manner so as to render the use of the mark likely to be taken as being used as a trademark.”

In contrast, the TM Act is much wider, Section 29(6)(d) states that, “For the purposes of this section, a person uses a registered mark if, in particular, he –

(d) uses the registered trade mark on business papers or in advertising.”

The Learned Division Bench while also making reference to Google France SARL and Google Inc. v. Louis Vuitton Malletier SA & Ors. ( [2014] EWCA Civ 1403) stated that the Ads Programme is Google’s commercial venture to monetize the use of its Search Engine for advertising. The use of trademarks as keywords for display of advertisements clearly amounts to use of the trademark in advertising within the meaning of Section 29(6) of the TM Act.

It further added, “The expression ‘in advertising’ as used in Section 29(6)(d) of the TM Act is not synonymous to the expression ‘in an advertisement’. It is not necessary that the registered trademark physically appears in an advertisement for the same to be used “in advertising”. The use of a trademark as a keyword to trigger display of an advertisement of goods or services would, in plain sense, be use of the mark in advertising.”

(ii) Will such use constitute infringement under the Act?

It is important to note that the Learned Single Judge considered the use of trademarks as keywords analogous to using the same as meta-tags, for the limited purpose of examining infringement. “A ‘Meta-tag’ is a list of words or ‘Code’ in a website normally hidden from human view. It acts as an index or reference source identifying the content of the website for search engine.” McCarthy on Trademarks and Unfair Competition, Volume 5 in § 25A:3 Whether such use amounts to infringement depends on the facts of the case. Courts are inconsistent on the issue.

| Kapil Wadhwa & Ors. v. Samsung Electronics Co. Ltd. & Anr | Use of a trademark in the source code as a meta-tag is illegal. |

| Amway India Enterprises Pvt. Ltd. v. 1MG Technologies Pvt. Ltd. & Anr | The use of the trademark as a meta-tag in advertising would amount to infringement of the proprietor’s trademark. |

| People Interactive (I) Pvt. Ltd. v. Gaurav Jerry | The defendant had “hijacked Internet traffic from the Plaintiffs’ site by a thoroughly dishonest and mala fide use of the plaintiffs’ mark and name in the meta tags of his own rival website.”, resulting in infringement of the plaintiffs’ mark and the effect of compromising and diluting its distinctive character. |

| Reed Executive Plc & Anr. v. Reed Business Information Ltd. and Ors. [2004] R.P.C. 40 767 | In the context of the use of meta-tags, “but purpose is irrelevant to trade mark infringement and causing a site to appear in a search result, without more, does not suggest any connection with anyone else.” |

Additionally, the Learned Division bench considered different sections of the act and stated that the use of registered trademark as a keyword, provided that it is absent any confusion, dilution, or compromise of trademark, would not amount to infringement of trademark. The rationale behind this is as follows:

- Section 29(1) is applicable when the use of a mark is likely to be taken as being used as a trademark. Since the use of trademarks either by an advertiser or by Google is not such as can be perceived as use of a trademark, the section is inapplicable to this case.

- Section 29(2) is only applicable when there is a likelihood of confusion, in the absence of which the section is rendered applicable.

- Section 29(4) is applicable when it is used in relation to goods or services which are not similar to those for which the trademark is registered and the mark allegedly infringed has a reputation in India and is facing damage to its distinctive character.

However, the Learned Division Bench addressed and upheld DRS’ contention of the Initial Interest Confusion doctrine which stated that confusion at the initial stage is sufficient to establish infringement even though an internet user may not be confused after visiting the site provided there is real likelihood of confusion. The Hon’ble Court said, “Section 29 of the TM Act does not specify the duration for which the confusion lasts. The trigger for application of Section 29(2) of the TM Act is use of a mark, which would result in confusion or indicate any association with the registered trademark. Thus, even if the confusion is for a short duration and an internet user is able to recover from the same, the trade mark would be infringed.”

A good example to understand this is Brookfield Communications, Inc. v. West Coast Entertainment Corporation 174 F.3d 1036 (9th Cir. 1999). Here, the defendant had used a term “MovieBuff”, which was the plaintiff’s trademark, as a meta-tag in the source code of the website. Thus, searching for the term “MovieBuff” on the internet would also yield results including links to the website of the defendant. The contents of the website were not misleading and did not provide any room for confusion. The Court used the following metaphor of a misleading road sign to explain the extent of confusion and for applying the Doctrine of ‘Initial Interest Confusion’:

“Suppose West Coast’s competitor (let’s call it “Blockbuster”) puts up a billboard on a highway reading – “West Coast Video: 2 miles ahead at Exit 7” – where West Coast is really located at Exit 8 but Blockbuster is located at Exit 7. Customers looking for West Coast’s store will pull off at Exit 7 and drive around looking for it. Unable to locate West Coast, but seeing the Blockbuster store right by the highway entrance, they may simply rent there.”

One of the notable criticisms to the analogy used is that in case of web browsing, the internet user could, by the click of a button, exit from the site on which he had landed. It would take a fraction of a second to do so and there would be no inertia or inconvenience in doing so if the internet user does not wish to remain on the site.

Apart from this, the doctrine relies on several other case laws which are mentioned below:

| Grotrian, Helfferich, Schulz, Th. SteinwegNachf v. Steinway & Sons 523 F.2d 1331 (2d Cir. 1975) | The Court accepted that the consumers had initially believed that Steinweg pianos were in some way associated with Steinway. However, at the time of purchase, the consumers were not confused and were fully aware that they did not have any relation or association with Steinway Pianos. Notwithstanding the same, the Court held that Steinweg had infringed the Steinway’s registered trade mark as the consumers had been deceived at the earlier stage. |

| Mobil Oil Corp. v. Pegasus Petroleum Corp 818 F.2d 254 (2d Cir. 1987) | Although the court found that there was little possibility that consumers would be confused at the time of entering into the transaction for oil; nonetheless, held that the defendant (Pegasus Petroleum) had infringed Mobil Oil’s trademark because it was probable that “…Pegasus Petroleum would gain crucial credibility during the initial phases of a deal. For example, an oil trader might listen to a cold phone call from Pegasus Petroleum… when otherwise he might not, because of the possibility that Pegasus Petroleum is related to Mobil.” |

| Promatek Industries, Ltd. v. Equitrac Corp. 300 F.3d 808 (7th Cir. 2002) | “By [defendant] placing the [plaintiff’s trademarked] term Copitrack in its metatag, consumers are diverted to its web site and [defendant] reaps the goodwill developed in the Copitrack mark. That consumers who are misled to [defendant’s] website are only briefly confused is of little or no consequence… What is important is not the duration of the confusion, it is the misappropriation of goodwill.” |

| People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals v. Michael T. Doughney 113 F. Supp. 2d 915 (E.D. Va. 2000) | In that case, the action was premised on the use of the domain name “peta.org”, which was linked to a site captioned ‘People Eating Tasty Animals’. ‘Peta’ is a well-known acronym for ‘People for Ethical Treatment of Animals’ – an American animal rights non-profit organisation based in Virginia. The court applied the Doctrine of ‘Initial Interest Confusion’ and found that misleading the parties to access the defendant’s website, would warrant interdiction. |

| Niton Corp. v. Radiation Monitoring Devices, Inc. 27 F. Supp. 2d 102 | The defendant had used a phrase which was identical to the texts on Niton Corporation’s website. The search for the phrase ‘Home Page of Niton Corporation’ yielded results that included pages from the defendant’s website. Preliminary injunction was granted as it found that there was a likelihood of confusion, which would mislead the users to believe that the defendant was the plaintiff or affiliated to it. |

| Tdata, Inc. v. Aircraft Technical Publishers 411 F. Supp. 2d 901 | The Court observed that the use of the competitor’s mark in meta-tags constitutes infringing use of the mark to pull consumers to Tdata’s website and the products it features, even if the consumers later realise the confusion. |

DRS Logistics also contended that internet users in India are not as sophisticated as those overseas and therefore, they are likely to believe that the advertisements reflected on the SERP have a connection and relate to the goods and services that are covered under the trademark. For this, the Learned Single Judge had placed reliance on Amritdhara Pharmacy v. Satya Deo Gupta AIR 1963 SC 449. Here, the Hon’ble Supreme Court had held that the question whether there was likelihood of confusion was required to be determined from the standpoint of a person of average intelligence and imperfect recollection. The Learned Division Bench however clarified that this standard was used in the context of determining whether the mark as displayed would evoke recall of the trademark. This is not the test propounded for use of an internet software tool or a device. It would be erroneous to proceed on the basis that although a person is using a mobile device, a laptop, a tablet or a desktop computer for surfing the internet and is aware of how to use an internet search engine like the one operated by Google; he/she would be unaware that an internet search engine is merely an indexing service and is capable of throwing all sorts of results.

So whether the use in this case will amount to infringement is a matter of speculation and for the High Court to decide as the matter progresses.

(iii) Can Google be held liable for contributory infringement in the given case?

There are two contentions which need to be tackled to ascertain the above question,

- Is it Google that is liable or the advertiser who has used trademarks as keywords?

To address the first contention, Google states that it merely permits advertisers to use keywords for display of sponsored links; it does not select the keywords. It claims that the Keyword Selection Planner is merely a tool which enables the advertisers to take an informed decision.

The Learned Division Bench however disagreed and found that Google is an active participant in promoting use of trademarks as keywords for the purpose of its Ads Programme. The fact that Google is a recipient of the bid amount; plays an active role in using its tools to suggest the most relevant keywords with the object and purpose of encouraging its use; is in full control of the decision – although made through the use of its proprietary automated system – as to which Ad to display at which page, leaves little room for doubt that Google is an active participant in the use and selection of keywords.

The question whether DRS has a right to demand that its trademarks not be used unauthorizedly for display of Ads is at the core of the dispute but there is no cavil that it is Google’s page that is displayed and that it displays the sponsored links (Ads). The corresponding responsibility of the selection of Ads displayed by it and the process used for the same, substantially, if not entirely, rests with Google.

The Learned Division Bench made reference to below mentioned cases that capture the essence of the controversy and lend a perspective on its various aspects.

| Rosetta Stone Ltd. v. Google Inc. 676 F.3d 144 (4th Cir. 2012) and 15 U.S.C. § 1114(a) | In respect of the claim for contributory negligence, the Court found that Rosetta had produced material relevant to its claim including material that reflected that Google was aware that some known infringers and counterfeiters would also bid for Rosetta’s trademarks as keywords.

It is also important to note that the US Court of Appeal noted that Google was using the mark, “in commerce” and “in connection with the sale, offering for sale, distribution, or advertising” as contemplated under the Lanham Act. |

| Rescuecom Corp. v. Google Inc. 562 F.3d 123 (2d Cir. 2009) | The Court rejected Google’s contention that the use of keywords was an internal use and therefore, did not qualify as use of a trademark and held that “Google’s recommendation and sale of Rescuecom’s mark to its advertising customers are not internal uses”. |

| Playboy Enterprises v. Netscape Communications Corp. 354 F.3d 1020 (9th Cir.2004) | Netscape allowed advertisers to display their advertisements to certain users depending on their internet search query by a method termed as ‘Keying’. It was alleged that banner ads were either not labelled or insufficiently labelled to enable the users to discern that the same were not associated with Playboy. The Court restrained Netscape from displaying banner advertisements by using Playboy’s trademarked terms. |

| 800-JR Cigar, Inc. v. GoTo.com, Inc. 437 F. Supp. 2d 273 | GoTo.com had adopted a model which monetized the priority in search results. The advertisers could purchase a higher priority on the search results when internet users entered JR Cigar’s name, which was also its trademark. The US District Court found GoTo.com’s use of JR Cigar’s trademarks as “use in commerce” under the Lanham Act. |

The Learned Division bench concluded that, “Google has actively participated in the infringement of the trademarks by use of the trademark as keywords and had taken no remedial steps on being made aware of the same, an action for holding Google contributorily liable for infringement may be permissible. Google’s policy to permit the use of trademarks as keywords heightens the level of its responsibility to take steps that such use does not amount to infringement. It is difficult to accept that Google has no responsibility if the Ads prioritized by it on the basis of use of trademarked terms as keywords, are found to be infringing the trademark. It is not necessary for us to consider this aspect in any detail at this interlocutory stage. The same would be a matter of trial provided DRS has laid a foundation for the action of contributory infringement in its pleadings and it produces evidence to establish the same.”

2. Can Google claim exemption as an intermediary under Section 79(1) of the Information Technology Act, 2000?

Section 79(1) states that, (1) Notwithstanding anything contained in any law for the time being in force but subject to the provisions of sub-sections (2) and (3), an intermediary shall not be liable for any third party information, data, or communication link made available or hosted by him. However, the safe harbour is not available to the intermediary if he selects the receiver of the transmission. Further, the exemption is provided if the intermediary observes due diligence while discharging its duties under the IT Act. Sub-section (3) of Section 79 of the IT Act also makes it amply clear that restriction of liability is not available where an intermediary has conspired, abetted, aided or induced the commission of an unlawful act.

It can hardly be accepted that Google can encourage and permit use of the trademarks as keywords and in effect sell its usage and yet claim the said data as belonging to third parties to avail an exemption under Section 79(1) of the IT Act.

It is also pertinent to note that prior to 2004, Google did not permit use of trademarks as keywords. However, Google amended its policy, obviously, for increasing its revenue. Subsequently, it introduced the tool, which actively searches the most effective terms including well known trademarks as keywords. It is verily believed that in the year 2009 Google estimated that use of trademarks as keywords would result in incremental revenue of at least US Dollar 100 million. (Email by Google’s project manager (Baris Glutekin) produced on record of the case of Rosetta Stone vs Google 676 F.3d 144 (US court of appeal for the 4th Circuit) and referred in an article Trademarks as Search Engine Keywords: Much Ado About Something?, 26 HARV. J.L. & TECH. 481 (2013) by David J. Franklyn & David A. Hyman.)

Google is not a passive intermediary but runs an advertisement business, of which it has pervasive control. Merely because the said business is run online and is dovetailed with its service as an intermediary, does not entitle Google to the benefit of Section 79(1) of the IT Act, in so far as the Ads Programme is concerned.

The Learned Division Bench after much deliberation has upheld the Learned Single Judge’s order and the reliefs granted by the Single Judge will remain in force till the matter reaches its conclusion.

The reliefs have been extracted below for reader’s reference,

“127. I must state here that the plaintiff can seek protection of its trademarks which are registered in view of Section 28 of the TM Act, but cannot have any right on surnames / generic words like Packers or Movers individually. Having said that in view of my above discussion, the applications are liable to be allowed, subject to final determination of the suit in the following manner:

(I) The defendant Nos.1 and 3 shall investigate any complaint to be made by the plaintiff to them alleging use of its trademark and its variations as keywords resulting in the diversion of traffic from the website of the plaintiff to that of the advertiser.

(II) The defendant Nos. 1 and 3 shall also investigate and review the overall effect of an Ad to ascertain that the same is not infringing / passing off the trademark of the plaintiff.

(III) If it is found that the usage of trademark(s) and its variation as keywords and / or overall effect of the Ad has the effect of infringing / passing off the trademark of the plaintiff then the defendant Nos.1 and 3 shall restrain the advertiser from using the same and remove / block such advertisements.”

It will be interesting to see how this matter proceeds and will surely have significant ramifications for Google, advertisers and competitors in the market.