In a 146-pager judgement, the Madras High Court on March 2, 2018 decided on the dispute between Star India Private Limited, Vijay Television against TRAI and others [Read Judgement here] wherein Chief Justice Indira Banerjee rendered the dissenting decision in favour of TRAI having exercised its powers within jurisdiction however holding that the clause putting cap of 15% to the discount on the MRP of a bouquet as arbitrary.

In view of the split verdict, the writ petitions would be placed before a third judge. As reported by Indiantelevision.com, now that the high court has delivered a fractured verdict, raising fears of a status quo and non-implementation of the TRAI tariff guidelines in certain sections of the cable distribution industry, the Supreme Court could, likely on Monday, take a view whether TRAI can go ahead and implement regulations or further judicial clarity is needed.

Issue in brief: The petitioners’ main challenge was that the jurisdiction of TRAI is to regulate and fix tariff limited to carriage or ‘means of transmission’ and it cannot be extended to ‘content’ which is governed under the Copyright Act, 1957 i.e. TRAI can regulate ‘carriage’ but not ‘content’.

The amended prayer of the petition read as under:

“to issue of Writ of Declaration or any other Writ, order or direction in the nature of a Writ of Declaration holding and declaring that the Provisions of the Telecommunication (Broadcasting and Cable) Services Interconnection (Addressable Systems) Regulations, 2017 notified on 03.03.2017 and the Telecommunication (Broadcasting and Cable) Services (Eighth) (Addressable Systems) Tariff Order, 2017 notified on 03.03.2017 to the extent that they have the effect of regulating, determining or otherwise impacting content creation, generation, exploitation, licensing and terms and conditions for exploitation of content and broadcast reproduction rights and in particular,

- Clauses 2(h), 2(j), 2(mm), 2(pp), 3 and 7 of the Telecommunication (Broadcasting and Cable) Services Interconnection (Addressable Systems) Regulations, 2017,

- Clauses 2(f), 2(h), 2(zg), 2(zh) and 3 of the Telecommunication (Broadcasting and Cable) Services (Eighth) (Addressable Systems) Tariff Order, 2017

are unconstitutional and ultra vires the provisions of the TRAI Act, 1997 inasmuch as they are beyond the scope of the jurisdiction of TRAI conferred under the TRAI Act, 1997 and consequently quash the same and pass such other Writ, order or direction as the Court may deem fit in the interest of justice in the circumstances of the case….”

All India Digital Cable Federation, Indian Broadcasting Foundation and Videocon d2h Limited intervened in this petition. Two intervenors, namely, All India Digital Cable Federation and Videocon d2h Limited were supporting TRAI, whereas the third intervenor, namely, Indian Broadcasting Foundation, supported the petitioners.

When asked by the Court to identify the clauses which according to the petitioners have the effect of regulating, determining or otherwise impacting content creation, generation, exploitation, licensing and terms and conditions for exploitation of content and broadcast reproduction rights, senior counsel Mr. P. Chindambaram appearing for the petitioners, gave the following seven clauses in the Interconnection Regulations and eleven clauses in the Tariff Order which he deemed would be appropriate to determine the constitutional validity and vires of these clauses in all.

Provisions of the Telecommunication (Broadcasting and Cable) Services Interconnection (Addressable Systems) Regulations, 2017 (“Interconnection Regulation”) which Regulate content:

| Sr. No | Provision | Ground |

| 1. | 6(1) All channels (pay channels and free-to-air channels) to be offered on a-la-carte basis. | Impinges upon broadcaster’s ability to package a TV channel. No such restriction on broadcaster under Copyright Act. |

| 2. | Second proviso to 6(1)- Bouquet of pay channels shall not have free-to-air channels.

– HD and SD variant of same channel cannot be in same bouquet. |

Impinges upon broadcaster’s ability to package a TV channel. No such restriction on broadcaster under Copyright Act. |

| 3. | Proviso to 7(2) – Bundling of third party channels prohibited. | Impinges upon broadcaster’s ability to package a TV channel. No sch restriction on broadcaster under Copyright Act.

|

| 4. | 7(4) – Broadcaster can offer discounts to distributor not exceeding 15% of MRP. | Directly regulates the pricing of a TV channel, thereby also regulating pricing of individual programmes. |

| 5. | First proviso to 7(4) – Sum of discount under 7(4) and distribution fee under 7(3) shall not exceed 35% of MRP. | Directly regulates the pricing of a TV channel, thereby also regulating pricing of individual programmes. |

| 6. | 10(3) r/w 6(1) – Mandatory to enter into agreement with DPO on an a-la-carte basis for pay channels. | Impinges upon broadcaster’s freedom to offer pay channels only as a part of bouquet and not as a-la-carte. No such restriction on broadcaster under Copyright Act. |

| 7. | 11(2) – Deemed extension of geographical territory. | Directly impinges the broadcaster’s right under 19(2) to designate the geographical territory of exploitation. |

Provisions of the Telecommunication (Broadcasting and Cable) Services (Eighth) (Addressable Systems) Tariff Order, 2017 (“Tariff Order”) which regulate content:

| Sr. No | Provision | Ground |

| 1. | 3(1) – All channels to be offered on a-la-carte basis | Impinges upon broadcaster’s ability to package a TV channel. No such restriction on broadcaster under Copyright Act. |

| 2. | 3(2)(b) – Declaration of MRP of a-la-carte channel | Impinges upon broadcaster’s freedom to offer pay channels only as a part of bouquet and not as a-la-carte. No such restriction on broadcaster under Copyright Act. |

| 3. | Second proviso to 3(2)(b) – MRP of all pay channels to be uniform across distribution

platforms. |

Under Section 33A read with Rule 56 of the Copyright Rules, 2013, broadcaster has the right to decide separate MRP for different category of

audience. |

| 4. | First proviso to 3(3) – Bundling of third party channels prohibited. | Impinges upon broadcaster’s ability to package a TV channel. For example, third party channels cannot be part of the same bouquet. No such restriction on broadcaster under Copyright Act. |

| 5. | Second proviso to 3(3) – MRP of pay channel in bouquet not to exceed INR 19/- | Directly regulates the pricing of a TV channel, thereby also regulating pricing of individual programmes. |

| 6. | Third proviso to 3(3) – Bouquet price shall not be less than 85% of the sum of a-la-carte prices of individual channels in the bouquet. | Directly regulates the pricing of a TV channel, thereby also regulating pricing of individual programmes. |

| 7. | Fourth proviso to 3(3) – MRP of all bouquets to be uniform across distribution platforms. | Under Rule 56 of the Copyright Rules, 2013, broadcaster has the right to decide separate MRP for different category of audience |

| 8. | Fifth proviso to 3(3) – Bouquet of pay channels shall not have free-to-air channels. | Impinges upon broadcaster’s ability to package a TV channel. No such restriction on broadcaster under Copyright Act. |

| 9. | Sixth proviso to 3(3) – HD and SD variant of same channel cannot be in same bouquet. | Impinges upon broadcaster’s ability to package a TV channel. No such restriction on broadcaster under Copyright Act. |

| 10. | 3(4) – Restriction on promotion of bouquets, restriction on time, restriction on frequency. | All these restrictions impinge broadcaster’s ability to commercially monetize his content. |

| 11. | 4(2) – Distributor to offer all channels on a-la-carte basis. | Indirectly impinges upon the broadcaster’s right to offer his channels to the customers only as a bouquet and not as a-la-carte.

|

Key Submissions of the petitioners:

- TRAI can regulate only carriage or means of transmission, but cannot regulate content.

- When section 33-A of the Copyright Act and Rule 56 of the Copyright Rules are extended and applied to Broadcast Reproduction Rights (BRR) with necessary modifications and adaptations, it becomes clear that the scheme to prescribe tariff for BRR is now specifically provided under the Copyright Act and that the authority in this regard is the Copyright Board under the Copyright Act. Television channel itself is BRR.

- Copyright Act and TRAI Act operate in two entirely different realms and the respective realms are clear watertight compartments. While Copyright Act deals with content and substantive right related thereto, TRAI Act deals with carriage of such content through various network and infrastructure, i.e., means of transmission.

- While TRAI Act has been enacted under Entry 31 of List I of Seventh Schedule of the Constitution of India (‘COI’), Copyright Act has been enacted under Entry 49 of the same list of COI and therefore, BRR which is akin to Copyright Act is also recognized under the Copyright Act which is traceable to powers under Entry 49.

Key submissions of TRAI:

- Madras High Court does not have territorial jurisdiction to entertain the instant writ petitions as according to TRAI, no part of cause of action has arisen within the territorial jurisdiction of this Court.

- Writ petitioners being foreign companies cannot maintain the instant writ petitions particularly when constitutional validity of certain clauses in a subordinate legislation are assailed inter-alia by taking recourse to Article 19 of COI.

- Writ petition of Star India, i.e., W.P.No.44126 of 2016 is hit by res judicata in the light of the reported judgment dated 09.07.2007 in Star India P. Ltd. Vs. Telecom Regulatory Authority of India and others [(2008) 146 DLT 455 (DB)] wherein a Division Bench of Delhi High Court held that fixation of tariff by TRAI for broadcasters is valid. There is no dispute that this judgment has attained finality.

- Writ petitions are hit by the doctrine of constructive res judicata too in the light of the ratio laid down in the judgment of TDSAT in Noida Software Technology Park Ltd. Vs. Media Pro Enterprise India Pvt. Ltd., being Petition No.295(C) of 2014, dated 07.12.2015, wherein BRR vis-a-viz regulations / tariff orders notified by TRAI were dealt with.

- As the writ petitioners have an efficacious alternate remedy of approaching the Telecom Disputes Settlement and Appellate Tribunal (‘TDSAT’ for brevity), the instant writ petitions under Article 226 of the COI are not maintainable in this court.

- Writ petitioners having participated in the consultation process and having requested TRAI to undertake the exercise qua said regulations and said tariff order cannot now be heard to contend that they assail certain clauses of the same as according to TRAI, writ petitions are hit by the doctrine of acquiescence.

- Writ petitioners are guilty of suppression as they have not disclosed the order suffered by them in the NSTPL case before TDSAT.

- There is no cause of action for the writ petitioners as according to TRAI, there is no pleading in the affidavits with regard to how the impugned clauses of said regulations and said tariff order have prejudiced, affected / infringed the rights of writ petitioners.

- Impugned clauses do not regulate the content as television channels are separate products by themselves. The activities (line of business activities) of writ petitioners in the light of uplinking and downlinking are pursuant to permission given by Government of India, which is traceable to Section 4(1) of the Indian Telegraph Act, 1885 and having obtained a license under the Telegraph Act, which stipulates that writ petitioners are bound by regulations of TRAI, writ petitioners cannot assail clauses in said regulations and said tariff order.

- Said regulations and said tariff order have been made in public interest keeping in mind the larger public interest and therefore, is protected by the public trust doctrine. In other words, it is the say of TRAI that airwaves / spectrum being public resources have to be uniformly distributed and that regulation of manner of carriage of electromagnetic waves of television channel and fixing of tariff for such offering is clearly protected by the public trust doctrine.

- Under the license agreement under Section 4 of the Indian Telegraph Act, 1885, there are provisions which say that broadcasters are bound by the regulatory authority, it’s regulations and orders.

Union of India submitted that TRAI is a specialized statutory body created under the statute and when it has come up with said regulations and said tariff order after detailed consultation and when TRAI emphatically says that said regulations and said tariff order have been made in public interest, the same should not be allowed to be assailed in writ petitions impelled by business interest of writ petitioners.

With respect to the objection on territorial jurisdiction and alternative remedy of appeal to TDSAT, the Court overruled the same for two reasons; one being that the impugned clauses are part of subordinate legislation made by a statutory body in exercise of its subordinate legislation under the TRAI Act. Territorial jurisdiction does not come in the way when constitutional validity and vires of central enactments are assailed. Secondly, technical objection is preliminary in nature and the writ petitions have been taken up for final disposal.

With respect to the plea that the writ petitions are liable to be dismissed as being hit by res judicata, the Court noted that in cases of this nature, doctrine of res judicata and constructive res judicata are not to be applied strictly to proceedings under Articles 226 and 32 of the COI. The Court also pointed out that the Star India vs TRAI judgement by the Delhi High Court was dated 9.7.2007 which was prior to the Copyright Amendment Act, 2012 and there were several submissions which were not available to the petitioners before the Delhi High Court then.

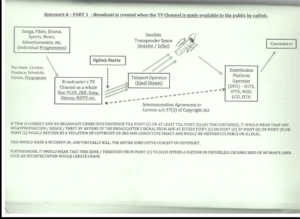

Chart produced by Petitioners:

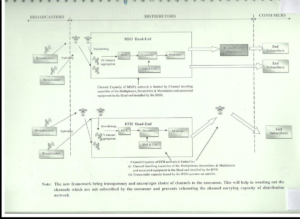

Chart produced by TRAI:

Referring to the chart, writ petitioners contended that the content of their programmes are produced at huge costs or are acquired at huge cost and submitted that unless they are permitted to price their television channels depending on the content, it would not be viable and they may not be able to survive in the industry.

TRAI contended that BRR comes into existence only when signal beamed by broadcasters (writ petitioners in the instant case) reaches the STBs of the end users and there is no BRR prior to that.

The Court observed that a close examination of impugned clauses in said regulations and said tariff order was that TRAI has not fixed any upper limit or cap for the writ petitioners in pricing their channels. Further more, TRAI has left it to the discretion of writ petitioners or similarly placed broadcasters to declare any particular channel as a pay channel. In other words, it is open to writ petitioners and other similarly placed broadcasters to declare any of their channels either as pay channel or as free to air (FTA) channel and only when the particular pay channel is put in a bouquet, it cannot be priced at more than Rs.19/- per month per subscriber.

While a plethora of judgements were relied on by each party, heavy reliance was placed on the Supreme Court’s decision in the matter of Cellular Operators Association of India and others Vs. Telecom Regulatory Authority of India and others [(2016) 7 SCC 703] (also popularly known as the ‘Call Drop Case’) to contend that the power under TRAI Act is non delegable and legislative in nature

Relevant extracts of the decision given by Justice M. Sunder:

In the instant case, that TRAI Act is in the realm of Entry 31, that Copyright Act is in the realm of Entry 49 are very clear. They are distinct and demarcated. Therefore, content of broadcasters, i.e., writ petitioners and other similarly placed broadcasters has to necessarily be regulated and fixation of tariff for the same has to necessarily be under Copyright Act.

It is common knowledge that the cost of production or cost of procuring various programmes will vary depending on artist, producer, nature of production and many other determinants. Therefore, TRAI while in one breath says that they are not regulating content, in the same breath compels the broadcaster to sell a channel at a particular price in a bouquet and is placing a cap on the price knowing fully well that the cost of content in many cases can be very high and far above the cap fixed by TRAI. Therefore, interalia, by this very simple illustration and analogy of bouquet of roses, we have no hesitation in coming to the conclusion that the impugned provisions of regulations before us have the effect of impacting and regulating content of broadcasters and as alluded to supra, it is the stated position of TRAI that they do not intend to and cannot regulate content.

The value of a programme in terms of its content can be determined only by the Copyright Board. The intention of the Parliament is clear and parliamentary wisdom in this regard is evident from the fact that barely a few weeks prior to the amendment to Copyright Act on 21.06.2012, the rules under the Cable Television Networks (Regulation) Act, 1995 (7 of 1995) were completely overhauled. We have no reason to believe that Parliament would not have noticed / taken into account overhauling of aforesaid Rules, while amending the Copyright Act. When these two are read in juxtaposition, it is very clear that while content of a programme and its value is governed by the Copyright Act and more particularly regulated by the Copyright Board under the Act, carriage or in other words, ‘means of transmission’ is governed by TRAI Act and is regulated by TRAI.

CONCLUSION BY JUSTICE M. SUNDAR:

Impugned provisions in the said regulations and said tariff order which touch upon content of the programmes of broadcasters are liable to be struck down as not in conformity with the parent Act / plenary Act. Therefore, clauses 6(1), second proviso to 6(1), proviso to 7(2), 7(4), first proviso to 7(4) and 10(3) of the said Regulations and clauses 3(1), 3(2)(b), second proviso to 3(2)(b), first proviso to 3(3), second proviso to 3(3), third proviso to 3(3), fourth proviso to 3(3), fifth proviso to 3(3), sixth proviso to 3(3) and 3(4) of the said tariff order are struck down as not in conformity with the parent act, i.e., TRAI Act.

The other impugned provisions, i.e., clause 11(2) in the said Regulations as also clause 4(2) in the said tariff order will continue to be in the books, but cannot be pressed into service for anything to do with the provisions which we have struck down supra. In other words, these provisions, i.e., clause 11(2) in the said Regulations as also clause 4(2) in the said tariff order can be operated if it can be operated for other provisions of the said Regulations and said tariff order, other than those which we have struck down.

DISSENTING DECISION BY CHIEF JUSTICE INDIRA BANERJEE:

Chief Justice Indira Banerjee dissented with Justice M. Sunder’s view that the provisions of the impugned Regulation and Tariff Order are not in conformity with the TRAI Act. In her view these provisions neither touch upon the content of programmes of broadcasters, nor liable to be struck down. However, she was in agreement that the clause putting cap of 15% to the discount on the MRP of a bouquet is arbitrary and not enforceable.

In the Chief Justice’s view, the amendments in the Copyright Act, have nothing to do with the inter se relationship between the broadcaster and the distributor in the activity of broadcast. It also does not deal with the price of a channel that an end consumer pays to the broadcaster. These provisions, after amendment, deal only with the broadcaster’s relationship with holders/owners of copyright/performer’s rights in the individual programme, which is re-broadcasted or reproduced. The impugned Regulations and/or the impugned Tariff Orders operate in a different sphere unconnected with Broadcast Reproduction Rights, governed by the Copyright Act.

The broadcasters can only transmit signals to the distributors named in the permission for re-transmission to the subscribers. It is, therefore, incorrect to say that the broadcast is complete when signal is given by the broadcaster to the distributor. That is only one step in the broadcast. The activity is complete when the distributor further re-transmits the signal to the end subscriber. The distributor and the broadcaster are the two arms in the activity of broadcasting.

Referring to Justice Sunder’s reliance on the Call Drop case, the Chief Justice observed that the Regulation impugned in the aforesaid case was not struck down on the ground of absence of transparency, but on the ground of manifest arbitrariness, as call drops attracted penalty on service providers even though they conformed to the quality standards laid down by the Quality of Service Regulations 2009, and such penalty did not advance the avowed object of the Regulation impugned, of quality control. The Supreme Court disagreed with findings of transparency arrived at by the High Court. While the Supreme Court was dealing with the same Regulation making power in the same statute, the Regulation impugned was different. A judgment rendered in the context of a different Regulation does not operate as a binding precedent in the case, where we are deciding inter alia validity of the impugned Regulation and the impugned Tariff Order.

![RECREATED VERSIONS & THE ISSUE OF MORAL RIGHTS [PART 2 -JAVED AKHTAR’S NOTICE TO T-SERIES, AMAAL & ARMAAN MALIK FOR RECREATED VERSION OF GHAR SE NIKALTE HI]](https://iprmentlaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/ghar-se-2-100x70.jpg)