The Recording Industry Association of America (“RIAA / Plaintiff”) filed two lawsuits against AI music generators, Suno and Udio (“the Platforms”), on behalf of record labels including Sony Music Entertainment, Universal Music Group’s UMG Recordings, and Warner Records Inc, and various others. These lawsuits, filed on June 24, 2024, allege that both companies used copyrighted music to train their AI models without authorization.

The lawsuit against Suno[i] was filed in the US District Court for the District of Massachusetts, while the lawsuit against Udio[ii] was filed in the US District Court for the Southern District of New York. A central issue here is whether the use of copyrighted songs to train AI constitutes copyright infringement, a question that US courts have yet to definitively address. It is important to look at the arguments made in the lawsuit here, in order to better understand the future implications of this case, as it may set an important precedent with effects in other jurisdictions.

Note: Because the complaints against Suno and Udio are almost similar, if not the same, the analysis here is based on the complaint made against Udio, with a few additions from the complaint against Suno wherever necessary based on the context.

Analysis of the Complaint

Background

The RIAA argued that AI companies, like all other enterprises, must abide by the laws that protect human creativity and ingenuity. There is nothing that exempts AI technology from copyright law or that excuses AI companies from playing by the rules.

RIAA argued that the Platforms, as generative AI services that create digital music files within seconds of receiving a user’s prompts, requires at the outset copying and ingesting massive amounts of data to train its software model in order to generate such outputs. This includes copying decades worth of “world’s most popular sound recordings”.

It was argued that the Platforms uses exceedingly general terms in public speeches and interviews, such as, they indicate that the Platform’s AI technology was trained on “a large amount of publicly-available and high-quality music” that is “obtained from the internet” and the “best quality music that’s out there”.

Allegations of infringement

RIAA alleged that the Platforms copied plaintiffs’ copyrighted sound recordings and integrated them into its AI model without any authorization. This copying allowed the Platforms to produce high-quality imitations of diverse music.

It was pointed out that the Platforms did not deny these allegations. Instead, the Platforms deflected, calling its training data “competitively sensitive” and asserting that it constitutes as “trade secrets,” while also asserting a “fair use” defense, this defence is used only when there is unauthorized use of copyrighted works.

There was ample evidence of the Platform’s unauthorized copying. Testing the Platform’s product with specific prompts, RIAA found that the generated outputs closely matched their copyrighted recordings, proving that such copyrighted recordings were used in training.

Even less specific prompts produced outputs resembling particular artists, indicating that Udio’s model was trained on plaintiffs’ copyrighted works. For example,

- In Udio, using the prompt “pop punk american alternative rock California 2004 rob Cavallo“, Udio generated “Subliminal Hysteria“, a file that allegedly shares many similarities with Green Day’s song, “American Idiot“.

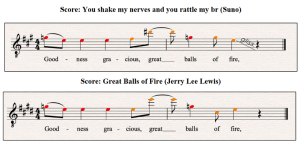

- In Suno, using the prompt “1950s rock and roll, jerry lee lewis, sun studio“, Suno allegedly generated the output “You shake my nerves and you rattle my br“, which includes a melody similar to Jerry Lee Lewis’ “Great Balls of Fire” (owned by UMG). The similarities for this song are strikingly similar as visible from the representation below:

It was submitted that the Platform generates music with such speed and scale that it risks overrunning the market with AI-generated music and generally devaluing and substituting for human-created work. Udio already makes a reported 10 music files per second, which amounts to 864,000 files per day, or just over 6,000,000 files per week, while Suno already has over 10,000,000 users generating music files using its product, with some outputs amassing upwards of 2,000,000 streams. Both the Platforms also profit heavily from their subscriptions.

Legal Assertions:

Plaintiffs cannot claim Fair Use:

RIAA argued that the Platforms cannot evade liability for willful copyright infringement by claiming fair use. Fair use promotes human expression through limited, unlicensed use of copyrighted works, but the Platform offers imitative machine-generated music, not human creativity.

Moreover, the Copyright law in the United States of America enumerates four factors to assess whether an unauthorized use is fair, none of which favour the Platform’s product. These factors are: (1) the purpose and character of the use; (2) the nature of the copyrighted work; (3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and (4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

It was argued that the Platform’s use is commercial, directly competes with RIAA’s music, and copies key expressive features of the copyrighted sound recordings. The Platform’s infringement further undermines both existing and potential commercial markets for selling, licensing, and distributing sound recordings.

The fair use doctrine has been coined an “equitable rule of reason” that balances various contextual factors to determine whether an unauthorized use of a copyrighted work is “fair.” But it was argued that the Platforms cannot launder its conscious stealing of the copyrighted recordings for commercial gain with an appeal to equitable principles.

It was also argued that the Platforms are eliminating the existing market for licensing sound recordings, as well as the future market for licensing sound recordings. Because rather than licensing copyrighted sound recordings, potential buyers would be interested in licensing imitative recordings generated by an AI at virtually no cost.

Cause of Action – Direct Infringement of Pre-1972 and Post-1972 recordings:

RIAA argued that the Platforms knowingly infringed the plaintiffs’ exclusive rights by reproducing RIAA’s copyrighted sound recordings without authorization, permission, license, or consent and using it to train their generative AI model. This includes the copyrighted works of Universal, Sony, and Warner. The Platform had no authorization, permission, license, or consent to reproduce or otherwise use such works.

Therefore, the Platforms’ acts of infringement of RIAA copyrighted works were alleged to be willful violations of the exclusive rights granted under the U.S. copyright law, specifically Section 106 (which are the exclusive rights of reproduction, adaptation, publication, performance, and display).

Even on knowledge of such fact, the Platforms engaged in such infringement, and therefore there was willful infringement of RIAA’s copyrights. (if the infringement is willful, the court may increase statutory damages up to a maximum of $150,000 per work infringed)

As a result of infringement by the Platforms, RIAA is seeking injunctive relief to stop any further infringement. They are also seeking either actual damages and both Suno’s and Udio’s profits, or statutory damages under the Copyright Act. Additionally, RIAA was seeking to recover their costs and reasonable attorneys’ fees.

Prayer

The Plaintiff in the prayer for relief pointed out the following points:

- Declaration of Willful Infringement: The plaintiffs are seeking a declaration that the Platforms have willfully infringed their copyrighted sound recordings of RIAA.

- Injunctive Relief: The plaintiffs are seeking a preliminary and permanent injunction to prevent the Platforms and its affiliates from further infringing the plaintiffs’ exclusive rights in their copyrighted sound recordings.

- Statutory Damages: The plaintiffs are seeking statutory damages of up to $150,000 per infringed work or actual damages including profit under the U.S. Copyright Act due to the Platforms alleged willful violations.

- Costs and Attorneys’ Fees: The plaintiffs are seeking an award of their costs and reasonable attorneys’ fees pursuant to the U.S. Copyright Act.

- Interest: The plaintiffs are seeking pre-judgment and post-judgment interest on any monetary award.

Conclusion

There is a large grey area out there with regards to the present issue, like in New York Times v. Open AI[iii] filed in United States Southern District Court Of New York where ‘The New York Times’ sued OpenAI and Microsoft for the unpermitted use of their articles to train GPT large language models. The NYT’s core allegation was that OpenAI was infringing on copyrights through the unlicensed and unauthorized use and reproduction of their works during the training of its models.[iv]

Some cases have seen some development, such as the case of author Sarah Silverman (Silverman et al v. OpenAI, Inc.), and the famous author Paul Tremblay (Tremblay et al v. OpenAI, Inc.), filed a lawsuit against OpenAI alleging that the company used their copyrighted books and works without taking their consent or giving them compensation to train their AI text generative system, ChatGPT. Out of all the claims brought forth by the Authors, the Court allowed their direct copyright infringement claim and unfair business practice claim to proceed to trial, but dismissed all other claims, with leave granted to the Authors for filing amended claims. You can access a discussion of this case here.

Final Thoughts

Sound Recordings, unlike words, is not something which already exists in the public domain that can be arranged in any manner you want. Recordings are made, using various tools, tweaked, pitched, edited, until a particular sound becomes a part of the sound recording. Words are publicly available information that can have a separate copyright once it is arranged and expressed differently. However, for sound recordings, only by arranging, or editing a piece out of the recording, it cannot be considered as a transformation.

Every use of a sound recording, even of few seconds, should require a license. Under the 2005 Sixth Circuit ruling in the U.S. in Bridgeport Music, Inc. v. Dimension Films,[v] the Court said that any unauthorized copying of the sound recordings no matter how trivial constitutes infringement. In this case, the rap group N.W.A., sampled a two-second guitar chord from a Funkadelic tune and used it five times in their song “100 Miles and Runnin”. In its opinion, the Sixth Circuit wrote: “Get a license or do not sample.”

It might be possible to equate this principle applicable to sound recordings to the present issue which is using sound recordings of RIAA to train the Platforms’ AI generative models.

Therefore, in my opinion, there is a fair chance that RIAA might win the case against the Platforms, a significant difference being that the infringed work is a sound recording, in contrast to literary or musical works.

End notes:

[i] https://www.riaa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Suno-complaint-file-stamped20.pdf

[ii] https://www.riaa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Udio-Complaint-6.24.241.pdf

[iii] https://nytco-assets.nytimes.com/2023/12/NYT_Complaint_Dec2023.pdf

[iv] https://harvardlawreview.org/blog/2024/04/nyt-v-openai-the-timess-about-face/

[v] 410 F.3d 792 (6th Cir. 2005)